MIRAI Researcher Profiles

Meet the exceptional researchers driving innovation at MIRAI! We’re kicking off a series of researcher profiles, starting with a spotlight on some of the chairs leading our Global Challenges Teams.

- Irina Mancheva

- Pierre De Wit

- Alexander Ryota Keeley

- Yoshihisa Hirakawa

- Jonathan Roques

- Takako Izumi

- Roman Selyanchyn

- Ranjula Bali Swain

- Shinobu Utsumi

Irina Mancheva

Assistant Professor, Umeå University

Swedish chair, GCT Resilient Cities and Communities

MIRAI has helped broaden both my network but also my experiences on

teaching and research.

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

I am fascinated by contextual factors, such as policies and regulations, characteristics of administrative systems, formal and informal institutions and this interest very much decides what research questions I am interested in investigating.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

I first experienced the MIRAI consortium when I presented my research at the R&I digital even in June 2021. After my presentation, I was contacted by a postdoc from Linköping University and we discussed research ideas of mutual interest. Together, we developed one idea and posted it on a MIRAI Sustainability digital platform for researchers from the MIRAI network to indicate their interest in it. That way we became a team of 5 researchers from Japan and Sweden that applied for a seed-funding project.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

I have been involved in several MIRAI events and initiatives during the years since I first got involved. I have found the consortium extremely useful and have only positive experiences from it. Both from the smaller digital matchmaking events and workshops, as well as the larger in-person events. The seed-funding project that we applied and received funding for started a research collaboration that is still ongoing. It helped me meet and exchange ideas with researchers from various disciplines, including chemistry, biology, biochemistry and economics. It also led to a successful short-term postdoc application from the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science in 2023.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and What unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

MIRAI has helped broaden both my network but also my experiences on teaching and research. Japan and Sweden have many similarities and differences. Comparing between the two, in both research but also generally in the academic setting, offers insightful research and professional perspectives. It has been a very helpful experience, especially as an early-career researcher. The biggest challenge I have encountered are the differing bureaucratic systems and how much more important details are in Japan.

Fun Facts

➡️ Person that inspired you to be a researcher: Dian Fossey

➡️ Hobbies and interests: All sorts of outdoor activities, reading,

(independent) movies, music (consuming, not creating 😊).

➡️ If you weren’t a researcher, what would be your dream job? That’s a

difficult one. Maybe working at an animal shelter. Or a diplomat (almost

became one).

Pierre De Wit

Senior Lecturer, Conservation Biology University of Gothenburg

Swedish chair, GCT Climate adaption, disaster, and risk management and

prevention

I saw this collaboration as an excellent opportunity to connect with

like-minded people from other universities both in Sweden and Japan.

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

Just like we humans are all different from each other, so are also all individuals of all other animal species in the world different from each other. Some are better at surviving heat waves than others for example. In some species there is a lot of variation among individuals, which makes the species as a whole more resilient to climate change (some individuals are likely to be ok, and they will reproduce and spread their genes to the next generation). But in some species, there is less variation among individuals – these will be much more sensitive to change. Knowing which species fall in these categories is really important to predict the future effects of climate change.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

I have a personal connection with Japan, and have spent a lot of time in the Tokyo area before the start of the MIRAI project. Therefore, I saw the project as a great opportunity to enhance my professional collaboration with Japan as well. In my field of marine biology, I know that there are many similar challenges facing both Sweden and Japan, and there are strong research environments in both countries. Therefore, I saw this collaboration as an excellent opportunity to connect with like-minded people from other universities both in Sweden and Japan.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

At the end of the first MIRAI period, I submitted a STINT initiation grant proposal together with researchers at Umeå University, Sophia University and Hokkaido University, which was funded. The aim of the project was to compare microbial biodiversity in wetlands in Sweden and Japan, north and south, in parallel, and to investigate the effects of human activities on biodiversity. Unfortunately, due to Covid, the project got delayed and is currently still ongoing, but we hope to be able to finish it soon! The first instance of the MIRAI project did not have any seed funding attached to it, which was a big problem. Now, with the seed funding available, there is a much greater chance of new collaborative projects arising from the network.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and What unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

As mentioned already, I work in the field of marine biology, and there are strong research environments in this field both in Sweden and Japan. Nevertheless, it has not been easy to find matching partners in Japan, as the topics of the project are so broad and open to interpretation from the partner institutions. However, I also think that the interdisciplinarity of the project also provides great opportunities to finding novel ideas for research that might not have been found in more traditional research collaborations.

How has your involvement with the MIRAI consortium influenced your perspective on international research collaborations, and can you share a moment when this collaboration led to an unexpected breakthrough or insight?

One reflection I have been nurturing lately is the seemingly different way in which our two countries think about the sustainable use of marine and terrestrial resources. In Sweden, we live in a land-dominated environment, with a relatively small sea surrounding the country. Human-caused effects are visible everywhere in the ocean around Sweden, and so the general public has a clear understanding that resources in the sea are limited and what we humans do affects the ocean in major ways. On the other hand, we tend to think of our aggressive forestry industry as something which is sustainable. Japan, on the contrary, is an island nation with a much larger population, surrounded by an enormous ocean. Here, sustainable use of land resources is much more prominent than in Sweden. However, the idea that ocean resources are also limited seem to not exist in the public awareness. I find these contrasting views very interesting, and it shows me that we can learn so much from each other.

Fun Facts

➡️ Person that inspired you to be a

researcher: Sir David Attenborough

➡️ Hobbies and interests: Hiking,

mushroom picking, diving, learning new languages, cooking and eating tasty

food, arts and music.

➡️ If you weren’t a researcher, what would be

your dream job? An astronaut – I applied to the ESA astronaut selection

program in 2021 and went through some of the selection steps, but did not go

all the way. That would be a dream, but I also love doing research – the

freedom to follow my interests and to manage my own job is amazing

Alexander Ryota Keeley

Associate Professor, Technology and Policy Department of Urban and

Environmental Engineering, Kyushu University

Japanese chair, GCT Resilient Cities and Communities

MIRAI has helped broaden both my network and my research experiences. I saw

this collaboration as an excellent opportunity to connect with like-minded

people from other universities both in Sweden and Japan.

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

A core pillar of my work involves assessing sustainability at multiple scales—corporate, national, and municipal. What many find surprising is how deeply I collaborate with these organizations to ensure real-world implementation, translating academic insights into tangible progress in sustainable practices. Whether I’m working with local governments or multinational corporations, I focus on building frameworks and methodologies that drive measurable improvements, bridging the gap between theory and practical outcomes.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

I’m driven by a strong belief in the power of interdisciplinary and international collaborations to tackle urgent global challenges. MIRAI offers an invaluable platform for connecting with experts across diverse fields. By engaging with researchers in Sweden and Japan, I’ve been able to expand my perspective, refine my approaches to sustainability assessment, and further amplify the societal impact of my work through shared knowledge and resources.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

I recently collaborated with researchers at Uppsala University to build a big data resource examining the relationship between sustainable investment and SDGs partnerships. This initiative leveraged cutting-edge data analytics to map how various stakeholders engage with sustainability goals and where the capital flows. Looking ahead, I aim to deepen my interdisciplinary work on sustainable investment, sustainability evaluation, and energy-related research through further cross-institutional partnerships under the MIRAI umbrella.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and What unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

MIRAI’s blend of disciplines and global perspectives creates a fertile ground for innovative solutions to complex sustainability issues. Collaborative efforts often spark new approaches to evaluating corporate, governmental, and community-level sustainability initiatives. At the same time, navigating different research norms, funding structures, and cultural expectations presents logistical hurdles. However, overcoming these challenges ultimately produces more robust, well-rounded research outcomes.

How has your involvement with the MIRAI consortium influenced your perspective on international research collaborations, and can you share a moment when this collaboration led to an unexpected breakthrough or insight?

MIRAI has reinforced my conviction that tackling critical global challenges—like sustainable investment and energy transition—requires a multinational, interdisciplinary lens. One memorable breakthrough came when a discussion on how various policies influence FDI flows at the global level, involving researchers from Sweden and Japan, revealed untapped intersections between SDGs partnership and FDI flows and data gap. This revelation propelled us to develop more comprehensive datasets and methodologies, ultimately shedding light on how international collaborations can drive sustainable growth and investment patterns. This data-building initiative became a breakthrough moment, demonstrating that meaningful progress often starts with recognizing and filling critical data gaps.

Fun Facts

➡️ Person that inspired you to be a

researcher: My father, Tim Keeley—a polyglot who speaks over 30 languages and

has excelled as both a linguist and a business scholar

(https://polyglotdreams.com/). His passion for exploring ideas across cultures

and disciplines shaped my own curiosity and academic pursuits.

➡️ Hobbies

and interests: Surfing. I’ve been fortunate enough to ride waves in 11

different countries and plan to keep exploring new coastlines whenever I have

the chance.

➡️ If you weren’t a researcher, what would be your dream

job?: If I had to pick another path, maybe I’d live off the grid, writing

songs by day and chasing waves by sunset. But for now, being a researcher is

exactly where I want to be.

Yoshihisa Hirakawa

Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya University

Japanese chair, GCT Health and an Ageing Population

At MIRAI, people do more than just find partners for joint projects—they

also build personal relationships beyond the projects, which contribute to

their research careers and overall professional development.

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

My research field is truly interdisciplinary. My research focuses on the well-being and quality of life of elderly individuals and their caregivers, exploring how to achieve these goals through interprofessional collaboration and a multidisciplinary approach. This inherently makes it easier to find research partners.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

It all started when my former professor suddenly told me, “Go to Sweden!” Until then, I had never considered international collaboration. However, once I experienced the warmth of the Swedish people—something that felt somewhat similar to the kindness of the Japanese—I found myself becoming more than just a research partner. Instead, I became a member of a community. I hope young researchers can have similar experiences.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

At MIRAI, I have worked on various research themes with many collaborators, including studies on the difficulties and discrimination faced by LGBTQ+ older adults, the effects of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), palliative care, dementia care, and interprofessional collaboration. It has been fascinating to notice both the differences and similarities in perspectives between Japan and Sweden. Additionally, through joint research, I have been able to learn new methodologies. As a senior researcher, I hope to provide young researchers with opportunities for networking and to share information on funding sources to help them start their research.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and What unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

Sweden is a leading country in social welfare, and there is much to learn, especially regarding human rights and discrimination—topics that are of great interest to me. One of the future challenges for MIRAI is that intersectoral collaboration is still developing. In other words, the integration between Ageing and other fields is still in the exploratory phase.

How has your involvement with the MIRAI consortium influenced your perspective on international research collaborations, and can you share a moment when this collaboration led to an unexpected breakthrough or insight?

Participating in the consortium has strengthened my communication with other researchers. While international collaboration itself is valuable, what surprised me was that through joint research with Swedish colleagues, I also built stronger connections with researchers in Japan. This kind of multidimensional exchange has been instrumental in sustaining long-term collaborations.

Fun Facts

➡️ Person that inspired you to be a

researcher: It was my former supervisor, a geriatric physician, who

introduced me to the world of research. My journey began with an unexpected

collaboration with the Acupuncture and Massage Association, which eventually

led to my doctoral thesis. In the medical research field, I found it

fascinating that such complementary and alternative medicine studies could

be accepted by international journals, sparking my deep interest in

research.

➡️ Hobbies and interests: Alcohol, Communication (casual

conversation), People-watching, Travel

➡️ If you weren’t a researcher,

what would be your dream job?: My dream was to become a doctor—and well,

here I am! Mission accomplished! Guess I need a new dream now. 😆

Jonathan-Roques

Associate professor, Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg

Swedish member, GCT Resilient cities and communities

prevention

Any recent publications or projects you want to share?

Last year we published a study showing that the marine anammox species, Candidatus Scalindua could tolerate high concentrations of nitrate, commonly found in recirculating aquaculture systems. This is another promising evidence that this alternative filtering technology can be used in land-base aquaculture systems in Sweden, to develop this sector in a sustainable way. Another of our study on the optimal phosphate condition for this bacterium allows us to know the optimal culture condition for this species was also accepted last month. Finaly, I am now in Japan for a study visit to the Environmental Preservation Engineering Laboratory, and the Coastal Hazards and Energy System Science (CHESS)-lab in Hiroshima, where my colleagues are developing low-cost buoy that we will use for monitoring of low-trophic aquaculture farms in Sweden.

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

Sometimes aquaculture can suffer from some misconceptions, false or outdated information. When thinking about aquaculture, people often picture open sea-cages, with salmon as main species, fed fish with a lot of fishmeal. There are many more to that. I work with closed, land-based systems where the water is filtered, and the wastes can be concentrated and transformed into valuable resources. I also look into alternative, low-trophic or circular protein sources to feed fish, instead of fishing wild fish to feed aquaculture fish. I also look into developing protocols to raise local species, in order to diversify the aquaculture sector, and ameliorate the quality of life of the cultured animals.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

I join the MIRAI in 2018, while participating at the sustainability workshop in Gothenburg. I am always looking at finding new collaborations. I had the opportunity to represent SWEMARC, the Swedish mariculture research center where I work. Both Japan and Sweden have a long culinary history with seafood, it was a great opportunity to find potential collaborations to develop sustainable seafood production.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

I am involved in three collaborative projects within the MIRAI. In 2018, I met Prof. Tomonori Kindaichi, from Hiroshima University, at the sustainability workshop in Gothenburg. I presented my research on recirculating aquaculture systems, and his work on wastewater treatment using the marine anammox bacteria Candidatus Scalindua. Together we elaborated the MARTINIS project, aiming at combing Swedish and Japanese technologies to ameliorate nitrogen waste removal in RAS. We have obtained some seed-funding from MIRAI and STINT to start our project, quickly followed by more funding from agencies like FORMAS and JSPS which allowed us to make this project idea into a real, MIRAI success-story. We have published four scientific articles and have presented our work at many national and international conferences. We are running experiments in both Sweden and Japan, involving young researchers from each countries. Four master students from our unique Nordic Master’s programme in Sustainable production and utilization of marine bio-resources (MARBIO) co-hosted by the universities of Gothenburg have successfully defended their master thesis on this project. I had the pleasure to welcome Naoki Fujii, a PhD student from Hiroshima University for two months last year. I will have the pleasure of visiting Prof. Kindaichi’s laboratory for two months as we recently obtained a JSPS invitational fellowship.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and What unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

Working trans and interdisciplinary can bring different perspectives and make us see things from a different angle. My Japanese collaborator has a background in engineering, and I am a biologist. Our different expertise is complementary and a key factor that made our project successful. Internationalization is very important I think from a professional and personal point of view. It opens up our mind and makes us grow as researchers, and as individuals. We discover and learn about new cultures, other ways of working and thinking, we learn and can also share our experiences, and we advance forward, together. For me, working in the MIRAI consortium brought more opportunities than challenges. I met many enthusiastic researchers from Sweden and Japan, and we were always supported by wonderful project managers. The seed-funding possibilities which appeared in the MIRAI 2.0 phase made it possible for projects to become real.

How has your involvement with the MIRAI consortium influenced your perspective on international research collaborations, and can you share a moment when this collaboration led to an unexpected breakthrough or insight?

When my colleague at the University of Gothenburg organized the Sustainability workshop in 2018, I joined out of curiosity, I did not expect that I will be representing the MIRAI at the world expo in Osaka in a few days. With the first phase, I could connect with Prof. Kindaichi and we obtained some seed-funding from STINT and other foundations to conduct our pilot experiment. During the MIRAI 2.0, we continued our joint experiments with Hiroshima and I further connected with the Marine Climate Change Unit from Prof. Timothy Ravasi at OIST. During this phase, the MIRAI consortium offered seed-funding opportunities for young researchers and allowed us to perform our experiments in Gothenburg and conduct a study visit in Okinawa. In the current phase of the MIRAI, I connected with the CHESS-laboratory from Prof. Han Soo Lee and we obtained a new seed-funding to develop a low-cost, smart buoy to monitor low trophic aquaculture sites in Sweden. I really grew as a researcher with the MIRAI, I started as an early career scientist, and I am now a member of the GCT, representing the University of Gothenburg. I am happy to share my experience with young researchers interested in international collaboration and try to promote international collaborations and exchanges, as I believe they are wonderful experiences.

Fun Facts

➡️ Person that inspired you to be a

researcher: I discovered research during my studies and had the opportunity to travel and do my first master internship thanks to my Professor Guy Charmentier, who really international exchanges. I joined Professor Gert Flik’s laboratory in the Netherlands for my Master and PhD, and later Kristina Snuttan Sundell in Gothenburg for my postdoc. Their dedication, passion and kindness inspired me to become and grow as a researcher, and teacher.

➡️ Hobbies and interests: I am also a badminton trainer at my local gym, and I like to pick-up wild berries and mushrooms in the Summer-Fall.

➡️ If you weren’t a researcher,

what would be your dream job?: Underwater photographer.

Takako Izumi

Professor, International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS), Tohoku University

Japanese chair, GCT Climate adaption, disaster, and risk management and prevention

Any recent publications or projects you want to share?

Takako, I., Miwa, A., Kumiko, F., Shaw, R. (2024) All-Hazards Approach: Towards Resilience Building, Springer (https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-97-1860-3)

Shaw, R., Izumi, T., Djalante, R., Imamura, F. (2025) Two Decades from the Indian Ocean Tsunami, Springer (https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-96-2669-4)

The project “Strengthening the Disaster Risk Reduction Capacity to Improve the Safety and Security of Communities by Understanding Disaster Risk” (https://jppsedar.net.my/about/), conducted in Malaysia, was completed in June 2024. The project focused on equipping local governments and community leaders with the skills and knowledge necessary to develop disaster risk education programs at the grassroots level, thereby building resilience from the bottom up.

It has achieved three significant impacts:

- Created a network of DRR collaborators linking government agencies and community actors, strengthening coordination and shared learning.

- Established a mechanism that enables local governments and communities to plan and implement community-based DRR initiatives.

- Fostered a mindset shift, with disaster risk reduction increasingly recognized as an integral part of everyday life.

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

Before joining academia, I worked for more than 15 years as a practitioner with UN agencies and an international NGO. During that time, my main responsibility was to coordinate international assistance provided by governments and organizations for emergency response and recovery. Through those experiences, I realized how crucial disaster preparedness and risk reduction are — the actions we take before a disaster can dramatically reduce damage and loss. That realization motivated me to shift from being a practitioner to becoming a researcher in disaster risk reduction (DRR).

In my research, I strive to incorporate the perspectives and practical realities I observed in the field — the voices of local people and stakeholders, as well as the need for realistic and feasible approaches to improve current systems. Recently, my focus has been on addressing increasingly complex risks and hazards. It is no longer sufficient to deal only with natural hazards such as floods, earthquakes, or typhoons. We must also consider technological hazards triggered by natural disasters, as well as compound and cascading risks that are becoming more frequent. This requires scaling up and strengthening our current risk management capacities. Furthermore, as societies evolve — with issues like aging populations and depopulation — our existing approaches must be adapted accordingly. I believe that integrating social science perspectives into DRR is becoming ever more essential to ensure our strategies truly reflect societal conditions.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

While we have established various collaborations with universities and stakeholders across Asia, our partnerships with European universities have been relatively limited. I have long been interested in understanding how disaster science is studied and practiced in Europe. I believe that Europe faces different types of disaster risks compared to Asia, and therefore adopts distinct approaches, tools, and research methodologies to manage them.

Through the MIRAI consortium, I hope to identify new areas and fields of collaboration where we can learn from each other’s experiences. By exchanging knowledge and perspectives, we can enhance our collective capacity for disaster risk management and develop more comprehensive, globally relevant approaches to reducing risk.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

Before joining GCTs, I had already received MIRAI seed funding in collaboration with Tohoku University and the Center of Natural Hazards and Disaster Science (CNDS) in Sweden. The main objective of this project was to initiate discussions for future collaboration and to strengthen exchanges between experts and young researchers.

As part of this initiative, delegates from both sides visited each other’s institutions to explore potential research areas for joint projects. Tohoku University also sent two students to participate in the summer school organized by CNDS, while one lecturer from Uppsala University visited Tohoku University to deliver a lecture at the summer school hosted by the International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS).

Through this collaboration, we established a solid foundation for continued exchange and identified several themes for future joint research within the MIRAI network.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and What unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

Interdisciplinary research is essential, and I am confident that the MIRAI consortium provides valuable opportunities to promote it. The members of each GCT come from diverse academic backgrounds and have different areas of expertise, even within the same thematic group. This diversity creates great potential for joint research and innovative ideas.

At the same time, I sometimes find it challenging to identify researchers whose interests and methodologies align closely enough for collaboration. However, I see this as a positive challenge — it encourages me to explore new perspectives, expand my research horizons, and initiate new interdisciplinary approaches.

In particular, I am interested in strengthening collaboration with researchers working on climate change, as climate-related risks are increasing globally. Integrating disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation is becoming increasingly important, and the MIRAI network provides an ideal platform to advance such interdisciplinary collaboration.

How has your involvement with the MIRAI consortium influenced your perspective on international research collaborations, and can you share a moment when this collaboration led to an unexpected breakthrough or insight?

Since I have not yet been directly involved in international research collaborations through the MIRAI consortium, it is difficult for me to share a specific example or moment of unexpected breakthrough. However, I see great potential in the consortium to create such opportunities.

MIRAI offers a valuable platform for connecting with researchers from diverse academic and cultural backgrounds, and I believe that this exchange of ideas will ultimately lead to new insights and innovative research outcomes. I look forward to experiencing such a moment in the near future as our collaborations deepen and evolve.

Roman Selyanchyn

Associate Professor, Platform of Inter-/Transdisciplinary Energy Research (Q-PIT), Kyushu University

Japanese member, GCT Materials for Energy Conversion and Storage

Any recent publications or projects you want to share?

Our current research focuses on capturing CO₂ directly from the air using advanced membranes. We explore how extremely thin selective layers — often just tens of nanometers — can dramatically influence gas separation performance. While much of our work remains at the level of fundamental materials science, we are gradually moving toward practical engineering applications. By fine-tuning membrane thickness and surface chemistry, we aim to achieve both higher productivity and better CO₂ selectivity against other gases.

Tell us something peculiar about your research.

A common misconception is that gas separation membranes work like sieves or filters with tiny holes that let certain gases pass through. In reality, most of these membranes are completely dense — gases like CO₂ don’t flow through empty spaces but rather dissolve into the material itself and then diffuse across it. That’s why the chemistry of the polymer is absolutely crucial. We study how molecular interactions within the material can favor CO₂ over other gases, which makes this field both scientifically fascinating and technologically demanding.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium?

I joined MIRAI thanks to the recommendation of my supervisor at Kyushu University, Prof. Shigenori Fujikawa. At that time, I was a postdoc eager to take part in any international activity. Initially, I thought it would be just another workshop or conference—but it quickly turned into something much more meaningful. Through MIRAI, I met inspiring researchers from Sweden and gradually built collaborations with Linnaeus University, Umeå University, Uppsala University, Karlstad University, as well as Stockholm University and KTH.

What I appreciate most about working with Swedish colleagues is their relaxed, open style of collaboration—less formal but very creative and efficient. MIRAI’s combination of research and social activities helps form real human connections, and over the years, I can say that I haven’t just built collaborations—I’ve made friends.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project within MIRAI?

One of the most meaningful connections/collaborations that grew through MIRAI is with Dr. Leteng Lin from Linnaeus University. We first met at a MIRAI workshop in Stockholm, where we were paired to develop a research idea from scratch. Since then, we have co-organized two workshops during the MIRAI Research and Innovation Week—one in Japan and one in Sweden—and have continued collaborating on several small projects both within and beyond MIRAI.

Our partnership has also become a friendship: we’ve visited each other’s labs several times, and now we’re part of the same Global Challenge Team related to Energy Materials. Communication has become completely informal and natural, which is exactly how collaboration should feel.

How does the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhance your research?

At Kyushu University, international collaboration is one of the key performance goals, and MIRAI has been essential in helping me maintain active partnerships in Sweden and develop new ones. Although I still hope to expand the scale of these projects, MIRAI provides a valuable framework that keeps these connections alive and productive.

I deeply admire Sweden’s strong expertise in forest-based research, wood science, bioenergy, and biopolymer materials—fields that are related to my own work on membranes and thin films. The interdisciplinary nature of MIRAI collaborations can be challenging at times, but that’s exactly what makes them exciting: they push us to think beyond the traditional boundaries of our disciplines.

How has MIRAI changed your view on international collaboration?

MIRAI has definitely changed how I view international collaboration. Over the years, I’ve compared traditional academic conferences with MIRAI’s more interactive format—and I strongly prefer the latter. MIRAI is not just a platform for presenting research; it’s designed to build genuine connections through creative group work, discussions, and social activities.

Starting a new international collaboration with someone you’ve never met is usually difficult, but MIRAI acts like a catalyst—it helps researchers build trust and friendship first, and once that bond forms, collaboration becomes a natural continuation of that catalyzed reaction.

Fun Facts/dream job

➡️ My research is deeply connected to CO₂ capture, and I often think about the broader meaning of our work in the context of climate change. Sometimes I wonder if laboratory research feels as immediately impactful as the work of an engineer installing solar panels on rooftops. If I weren’t a researcher, that might actually be my dream job—something tangible and directly contributing to the clean-energy transition.

Still, I believe that through international collaborations like MIRAI, we can achieve an even greater impact—by connecting science, technology, and people across borders.

Ranjula Bali Swain

Professor, Center for Sustainability Research (SIR), Stockholm School of Economics

Swedish member, GCT Materials for Energy Conversion and Storage

Any recent publications or projects you want to share?

2025 Bali Swain, R. and Dobers, P. (eds), Handbook of Sustainable Development Goals: Research, Policy and Practice, Routledge, April 2025.

2024 Huang L., Bali Swain, R., Jeppesen, E., Cheng, H., Zhai, Panmao., Gu, Baojing., Barcelo, D., Lu, J., Wei, K., Luo, L., Wang, F., Wang, H., Zeng, J.,Guo, H. Harnessing science, technology, and innovation to drive synergy between Climate Goals and the SDGs, The Innovation, 100693, September 02, 2024.

https://www.cell.com/the-innovation/fulltext/S2666-6758(24)00131-0

2024 Luo L., Zhang J., Wang H., Chen M., Jiang Q., Yang W., Wang F., Zhang J., Bali Swain R. et al. Innovations in science, technology, engineering, and policy (iSTEP) for addressing environmental issues towards sustainable development. The Innovation Geoscience 2(3): 100087.

https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2024.100087

Tell us something peculiar about your research, something people would regularly not know or understand.

Last Night in Sweden, is actually a peer-reviewed publication using Gaussian processes to study Swedish municipal demographics and criminality.

What inspired you to join the MIRAI consortium, and how do you see this collaboration benefiting your research goals?

Possibility for interdisciplinary collaborative research.

Can you share an example of a collaborative project or initiative within the MIRAI consortium that you have been involved in, or what future opportunities do you foresee, hope to establish, within the consortium?

Currently working on a joint publication on Decarbonizing the energy system.

How do you think the interdisciplinary and international nature of MIRAI enhances your research, and what unique challenges have you encountered while working within the MIRAI consortium?

Regular meetings, joint events, and research exchange visits are great. Expect further resources.

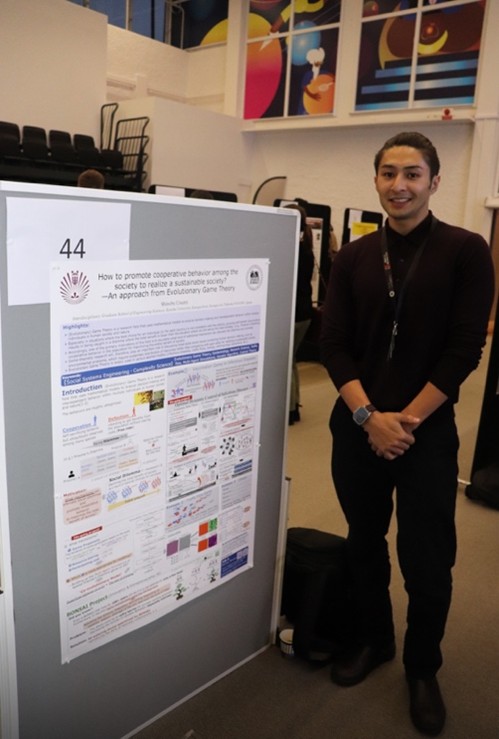

Shinobu Utsumi

Ph.D. Student, Interdisciplinary Graduate School of Engineering Sciences (IGSES), Kyushu University, Japan

R&I Week 2023 and Winter School 2024 participant

Could you tell us about your current research?

I’m drawn to exploring the universal laws hidden behind social and natural phenomena, which I tackle from a physics and mathematical perspective. My research spans multiple interdisciplinary themes: How do infectious diseases spread through human populations? How are people connected? Why do cooperation and defection emerge? More recently, I’ve also been working on an intriguing project—using applied mathematics to uncover the geometric beauty of bonsai trees.

How did your connection with Sweden and MIRAI begin?

It all started with my exchange program at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in 2022. I was fortunate to have a connection with a professor there, which allowed me to participate not only in coursework but also in an actual ongoing research project. After returning to Japan, I kept thinking, “I’d love to go back to Sweden someday (in the summer season),” and “I want to maintain my connection with Swedish researchers.” Thus, when I discovered MIRAI Research & Innovation Week (at Umeå University, 2023) through a university call for applications, I applied right away. Additionally, a part of my motivation was a desire to give back: having received so much support from the university during my exchange program, I wanted to actively contribute to Kyushu University’s international initiatives. Including the participation in MIRAI Winter School the following year as well, being continuously involved in an international program between Japan and Sweden has been an invaluable experience for me.

What left the strongest impression on you at R&I Week?

What struck me most was the remarkable “breadth and depth” of research fields represented. It’s rare, even in Japan, to have researchers from such a wide range of fields gathered in one place, and the discussions in each field were genuinely substantive. At first, the differences in our disciplines made detailed conversations challenging, but as we spent the week gradually deepening our discussions, unexpected discoveries emerged, and I was also able to have the kind of rich conversations that only doctoral students can share. Another major takeaway was the opportunity to interact with people beyond academia—representatives from JST, JSPS, and Japanese & Swedish industry. I also learned a great deal about funding opportunities abroad, which dramatically expanded my sense of what’s possible for my research career.

Is there any memorable experience from the 2024 Global Challenges Winter School?

My encounter with a doctoral student from OIST, who was my roommate during the Winter School, stands out in particular. Although our research fields were somewhat different, we spent the entire week discussing in depth not just research, but also life beyond the lab. As it turned out, his specialty was epigenetics, and he became very interested in one of my research sub-projects: “Digital twinning and the science of geometric beauty of Bonsai.” He suggested, “What if we added an epigenetic analysis approach?” If we both survive as researchers, I’d love to make that collaboration happen someday. Beyond that, a researcher in Culture & Industry expressed interest in following the progress of my work on digitalizing Japanese bonsai culture, and a psychology researcher mentioned wanting to study the psychology behind wabi-sabi through the lens of bonsai. At the time, I was also starting to think about my career after completing my PhD, so meeting researchers abroad with diverse values and career paths gave me a valuable opportunity to reflect on my own direction.

What challenges did you face conducting research abroad, and how did you overcome them?

During my master’s exchange program, I definitely felt the challenge of communicating in English. It was never my strong suit, and on top of that, I was also venturing into an unfamiliar research field, so I was overwhelmed by all the terminology I’d never heard before. (Honestly, I probably would have struggled even in Japanese…) But after a while, I realized that the local students weren’t speaking perfect English either, and they weren’t waiting until they fully understood everything before starting experiments. So I thought, why not ease up on myself and just try what I can at this stage? From that point on, the hurdle for taking on new challenges got lower. Even after returning to Japan, I developed a positive cycle of thinking, “I’m not sure if I can do it, but let’s just try first.” I believe this mindset has led to my continued applications to MIRAI and other competitive fundings.

What do you hope for from MIRAI going forward? Are there any areas you feel could be improved?

I think the MIRAI community would be strengthened if past participants could continue attending events even after R&I Week or Winter School ends. Of course, continuously bringing new researchers into the MIRAI community to expand “horizontal connections” is important. But at the same time, I feel it’s equally important to strengthen “vertical connections” that allow past participants to stay involved. Having participated in several MIRAI programs myself, I noticed that the group of participants changes each time, which can make it difficult to build lasting relationships. If there were events where Winter School or R&I Week alumni could reunite a few years later, those relationships could deepen further, and with everyone having advanced in their positions and gained more autonomy, collaborations might emerge more naturally. I believe such reunions would make the MIRAI consortium an even more robust and effective platform.

Do you have a message for students in Japan who are considering taking on challenges abroad?

If a program catches your interest or an event catches your eye, please don’t overthink it—just go ahead and apply! I certainly don’t consider my own international experiences sufficient, and in fact, I believe the real excitement of going abroad as a researcher comes after earning a PhD. Let’s share exciting research with the world together—through MIRAI!